Frozen in Time: A History of The Popsicle

Frozen in Time: A History of The Popsicle

BY CARA STRICKLANDIt’s hard to imagine a more charming origin story for the Popsicle: an eleven-year-old California boy named Frank Epperson concocts a drink out of powered soda and water, and accidentally leaves it outside, complete with a forgotten mixing stick. In the morning, the contents of the glass were frozen solid, and like any self-respecting eleven-year-old, Frank loosened it from the glass and tasted it, pronouncing it delicious. He called it an “Epsicle,” a blend of icicle, and his own name. Over the years, this story has been told in many versions, reliant on a child’s memory, and likely, a marketing team, but the main points remain fairly constant.

In the early 1920s, when Frank was a real estate broker, he was inspired by other frozen novelty treats (like the Eskimo Pie, which was patented in 1922), and began to optimize his invention for the market. If you’ve tried making your own frozen treats on a stick, you know that the consistency is different than a professional ice pop. Frank began to freeze the popsicles quickly, instead of waiting for them to harden over time, which allows the ingredients to settle. He also began to freeze them in long cylinders, giving them their iconic shape.

As a newly minted entrepreneur, Frank and his wife took a supply of Epsicles to a Fireman’s Ball and ate them conspicuously during the evening. Somewhere along the way, the name changed. One popular story is that Epperson’s children referred to the treats as “Pop’s Sicles” and another suggests that the “pop” comes from the sound made when it left the glass.

In 1923, Frank got together with employees of the Loew Movie Company to form Popsicle Company and immediately began selling them in amusement parks, where they were very popular. Although Epperson was involved with one Popsicle Company he didn’t trademark the name and another came on the scene in 1924, purchasing operating rights from the original. Frank patented his process in August of 1924, but sold all rights to the Popsicle company in early September of that year. “I was flat and had to liquidate all my assets,” he told the San Francisco Tribune just a few years before his death at 89. “I’ve never been the same since.”

You might remember summer days spent sucking all of the flavor out of a Popsicle, leaving only ice left on the stick, but it might surprise you to know this was part of the original marketing plan.

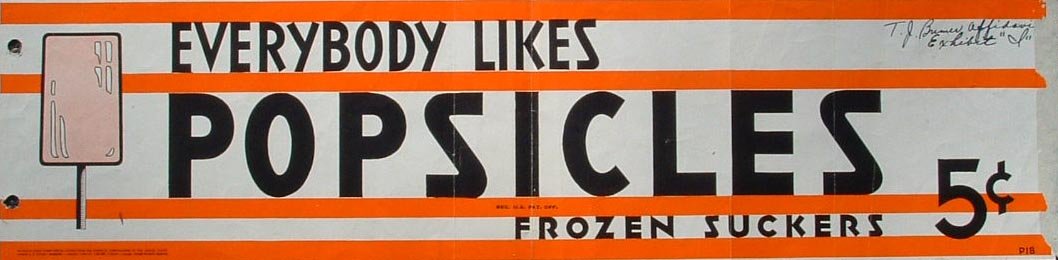

When Epperson patented his “frozen confection,” he suggested that since the flavoring would melt faster than the water, it could be thought of as a “refreshing drink,” he adds that the confection can be eaten in its entirety off the stick, almost as an afterthought. Early Popsicle ads called it “the drink on a stick.” It was this distinction that kept Popsicle and Good Humor on good terms in the beginning. The two companies had an agreement that though they would both sell frozen treats on sticks, one would be ice cream based and the other syrup, sugar and water based.

When the Great Depression hit, many people couldn’t afford to buy a Good Humor Bar for 10 cents, but they could swing a Popsicle for half the price. Dairy prices were going down, and Popsicle wanted to increase their flavor base. They ended up in court with Good Humor arguing for the right to produce ice milk Popsicles. Good Humor was loathe to give up a potential for profit, they had a 5 cent “Cheerio Bar” in production.

Although it was against their agreement, Popsicle started making ice milk Popsicles in the early 1930s, in a keystone shape (which looked a lot like a Good Humor bar). The battle with Good Humor included 32 state regulator’s comments on the definition of sherbet (which was allowable in a Popsicle, according to the agreement).

Eventually, Popsicle was allowed to continue manufacturing ice milk pops, allowing for the birth of the Fudgicle (later Fudgecicle) and many flavors of Creamsicles. The new shape also brought about an important development in the classic Popsicle, especially in the tight economic climate of the Depression. Popsicle fit two sticks into the keystone-shaped pops and advertised that they were perfect for splitting apart and sharing with a friend, all for just 5 cents. When the two-stick Popsicle went off the market in 1986, ostensibly because many mothers felt that they were too messy, the decision was met with public outcry, and a declaration from the Canadian division of Popsicle promising that they would not follow suit.

In the past few years, ice pops have gone gourmet. Venture to a farmer’s market, and you’ll find pops in flavors like chocolate avocado, Sriracha strawberry, and basil lemonade. Some cities have ice pop shops, and paleterias (paleta is the Spanish word for ice pop) rather like cupcakeries, which feature rows of beautiful pops in exotic rotating flavors.

It’s hard to imagine a time when “frozen suckers” and “a drink on a stick” were so novel to consumers, when the sound of a Good Humor truck was a new and exciting sound. But this summer, as you unwrap a gourmet pop, or bite into a classic, take a minute to think of Frank Epperson, and the accidental discovery with such sweet results.